CLIENT WORK: Barry Ace’s “How can you expect me to reconcile, when I know the truth?” (2018)

This work is dedicated to the memory of all children of these residential schools and their families. It is a call for debwewin (truth) and public awareness about this devastating scar on Canada’s history. We must never forget what happened at these schools, and Canada must fully address and implement the Calls to Action tabled by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission if we are ever going to collectively heal.

During his 2018 residency at the Ontario College of Art and Design University (OCADU) Barry Ace (www.barryacearts.com) created How can you expect me to reconcile, when I know the truth. The work, produced for OCADU’s Indigenous Visual Culture Program and their Nigig Visiting Artist Residency, was later installed from April 12-15, 2018 in Stockholm, Sweden as part of the group exhibition PUBLIC DISTURBANCE: Politics and Protest in Contemporary Indigenous Art from Canada curated by Galerie SAW Gallery for Supermarket 2018 Stockholm Independent Art Fair.

As with much of Barry’s work there is a biographical root. How can you expect me to reconcile, when I know the truth references his own family’s story of the impact of Canada’s Residential School System. An archival image of his Great Aunt Melvina holding his father, Cecil, as a baby has been printed on a piece of organza cloth to evoke a ghost-like translucency. In this sweet image there is no trace of the bitterness about to befall them at the hands of the Canadian State.

As with much of Barry’s work there is a biographical root. How can you expect me to reconcile, when I know the truth references his own family’s story of the impact of Canada’s Residential School System. An archival image of his Great Aunt Melvina holding his father, Cecil, as a baby has been printed on a piece of organza cloth to evoke a ghost-like translucency. In this sweet image there is no trace of the bitterness about to befall them at the hands of the Canadian State.

In light of the recent uncovering of more than a thousand unmarked children’s graves at various residential school sites, the work takes on an even more anguished implication. Intentionally layered into it’s structure is the story of one family, in a work that was originally created to honour the stories of the countless victims of Canada’s genocide.

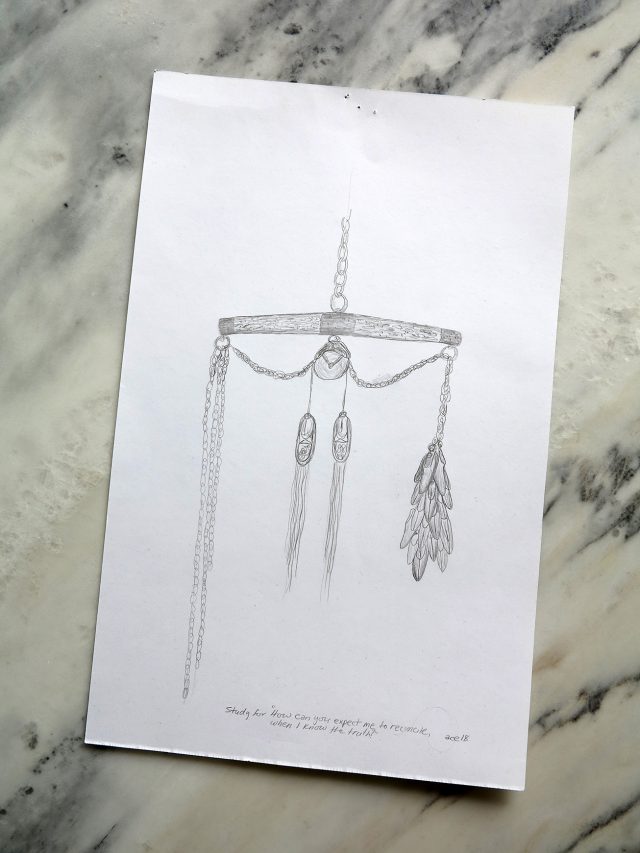

Although markedly changed from the prepatory drawing of the work above, the final iteration is nonetheless haunting. Under the organza, a linen cloth has been wrapped around a tikinagan (cradleboard in Anishinaabemowin), a utilitarian object used to carry babies but also most often designed with beautiful motifs, an important part of the material culture of the Anishinabeg as well as other Indigenous nations.

The installation consists of a child’s cradleboard covered with linen, that references an early 20th century photograph that I sourced from the Smithsonian Institution’s photographic collection depicting a cloth covered cradleboard that was attached to a rope and suspended from the ceiling of a collections storage room. This image evokes for me a strong sense of loss, in particular the loss of the family and stories to which it once belonged, and the information about the maker. Like the majority of museum pieces that were collected from Indigenous peoples, they have lost the song, story, dance, maker and lineage that each object once carried.

In the uneven yoke one is reminded of the scales of in/justice as well as the weight of grief from so many young lives lost. Attached to the thick hemp rope are the shapes of tiny moccasin-like shoes made from transparent bronze mesh. Some beaded and some left without, they have been molded off of a tiny antique wooden shoe form. Ace adds, “The antique shoe form is a colonial object and shaping the wire around these references the impact and molding of colonialism and assimilation.” Where the rope pools more shoes are entangled. On the wall behind – debwewin – a straightforward demand for truth.

View more images of How can you expect me to reconcile, when I know the truth here and visit Barry’s Nigig News posts on OCADU residency as well as his recent post revisiting his reason for this work.

ARTIST STATEMENT:

“How can you expect me to reconcile, when I know the truth?” is a response to the impact of residential school on my family. In the 1920s, children from Manitoulin Island were transported in a wooden dory boat called the Red Bug that was towed by a rope behind a motorized vessel called the Garnier. Vast numbers of Anishinaabe children were transported from the island to the mainland and segregated into two Jesuit-run boarding schools: the boys in Saint Peter Claver and the girls in Saint Joseph’s.

The installation consists of a child’s cradleboard covered with linen, that references an early 20th century photograph that I sourced from the Smithsonian Institution’s photographic collection depicting a cloth covered cradleboard that was attached to a rope and suspended from the ceiling of a collections storage room. This image evokes for me a strong sense of loss, in particular the loss of the family and stories to which it once belonged, and the information about the maker. Like the majority of museum pieces that were collected from Indigenous peoples, they have lost the song, story, dance, maker and lineage that each object once carried. They only exist now as “objet d’art.”

For this work, I have replicated a cradleboard and overlaid it with a bolt of linen and lashed it in place with rope. Laid on top of the cradleboard is an historical photograph taken of my great-aunt Melvina McGregor (Sagamok First Nation) holding my father Cecil Joseph Ace (M’Chigeeng First Nation) as a baby taken circa 1922 by my grandmother Mary McGregor-Ense-Ace. The photograph has been printed directly on transparent organza fabric to evoke a ghost-like image. Also printed on the organza is an image that I sourced from the Jesuit Archives in Montreal of the original survey drawing of the two schools along with photographic images of Saint Peter Claver and Saint Joseph’s.

The hemp rope used to suspend the cradleboard is similar to the rope that was used to pull an open boat behind the motorized Garnier. This open boat was called the Red Bug and was used to transport children from Manitoulin Island en route to Spanish, Ontario. The thick hemp rope extends from the cradleboard through two wooden pulleys attached to a wooden yoke that together reference the nautical and the burden of assimilation. Cascading down the rope that pools and coils on the floor are small bronze wire shoe forms that are molded from a child’s wooden shoe last. Some of these wire moccasin-like shoe forms are adorned with deer-hide fringe and electronic components with glass beads to form Anishinaabe floral motifs. The shoes are held transparent and hollow to represent the impact of assimilation and cultural loss, while the shoes that have partial floral motifs represent some aspects of the culture and language that survived to be passed on to future generations. Some of the moccasins are left blanket representing those who died at these schools. The hide fringe reference trail dusters that were once affixed to the heel of moccasins that dragged behind the wearer to erase evidence of their tracks. But these dusters are falling forward representing the experiences and stories of these children that must never be forgotten or erased.

The vinyl text mounted on the wall spells out Debwewin meaning Truth in Anishinaabemowin.

Barry Ace (2018)

TOP IMAGE: Photograph of prepartory drawing for “How can you expect me to reconcile, when I know the truth?” by Leah Snyder of drawing by Barry Ace. Collection of Leah Snyder.

OTHER IMAGES: Courtesy of Barry Ace (view more images of the work here and here)

No Comments