PUBLICATION: Essays for Barry Ace’s Digital Catalogue with Heffel

Leah Snyder of The L Project was invited to contribute these essays, based on her personal interviews with the artist and through her own insightful and well-researched approach to writing. She has creatively captured the meaning and intent behind each of Ace’s works that when read together, delve deep into the cultural context and also reveal outward connections to his expansive oeuvre. Leah has worked closely with numerous artists and arts organizations over the years and has written extensively on culture, technology and contemporary art, most notably, her recent work as a contributing writer to the National Gallery of Canada’s Magazine.

(source: Heffel’s Spring Newsletter launches a new online gallery space for artist Barry Ace)

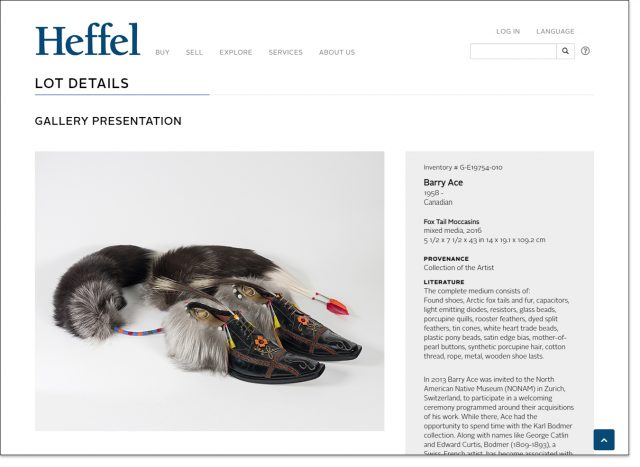

During the month of March I had the pleasure of spending time interviewing client Barry Ace (www.barryacearts.com). Since 2014 I have worked with Barry to design and build a robust digital archive of his work. With this current commission from Heffel (www.heffel.com), Canada’s leading art auction house, I was presented with the opportunity to go into a deep dive on his work. Now representing artists for private sale, including Canadian greats such as David Blackwood, the Estate of Joe Fafard and the Estate of Betty Goodwin, he is the first Indigenous artist added to their roster. After many years in dialogue with Barry and observing the way his work is received by both Indigenous and Non-Indigenous audiences it has been a highlight moment in my own career to be able to synthesis it all, including looking at how he has incorporated digital technology into his work propelling a distinct and stunning Anishinaabe aesthetic into the 21 st Century and beyond.

Below, I have highlighted quotes that capture the essence of Barry’s work. Click on the links to read the complete essays and view more lush images of his work or view the full catalogue listings here.

A note on the research of the gashkibidaagan (plural – gashkibidaaganag) or bandolier bag, I am grateful to Marcia Anderson for her scholarship on its history published in the informative and visually stunning book – A Bag Worth a Pony: The Art of the Ojibwe Bandolier Bag. I am indebted to the knowledge she has gathered together. For anyone desiring to know more on the material culture of the Anishinaabeg and other Woodland tribes, her book provides a rich and informative experience.

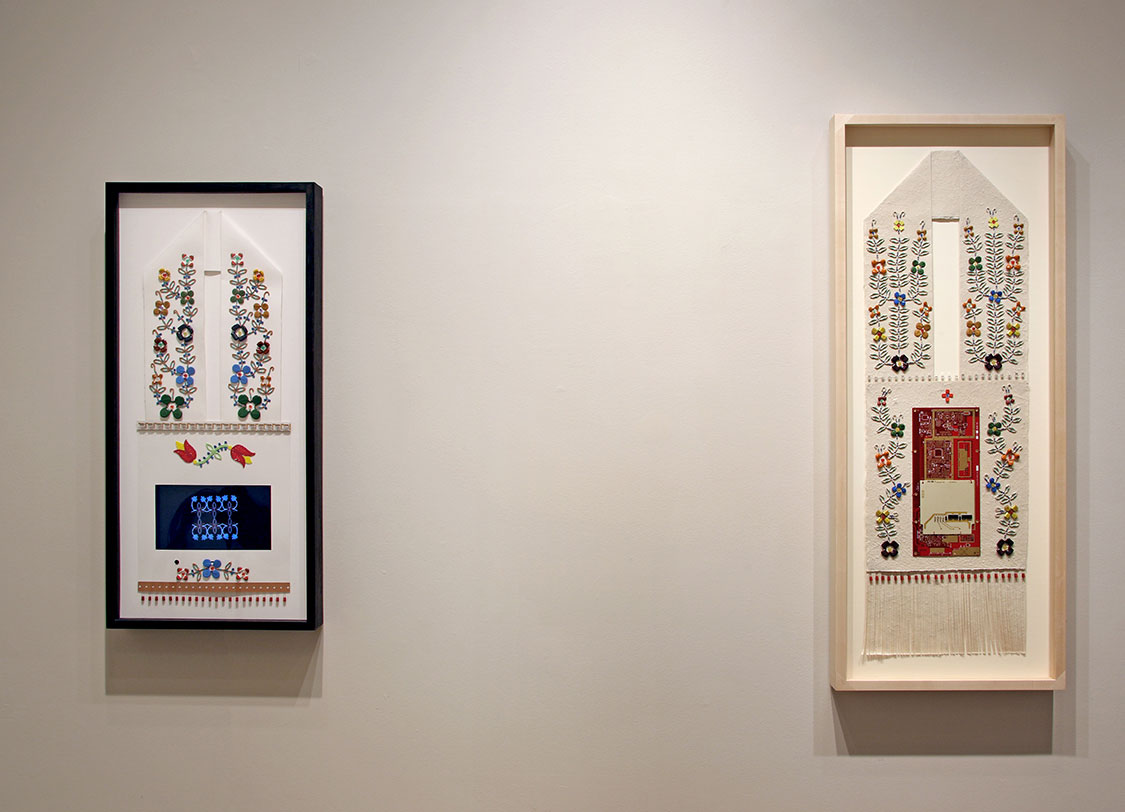

IMAGE: Left, Transformation Bandolier and Right, Waawaashkesh Dodem (Deer Clan) Automata Bandolier; Photo courtesy of Heffel Fine Art Auction House (view larger)

WAAWAASHKESH DODEM (DEER CLAN) AUTOMATA BANDOLIER

Ace articulates his combination of myth and electronics through the creation of a new portemanteau – the mythotronic. Continuing the motif of historical and contemporary convergence, Ace’s (re)presentations of Anishinaabe cosmology “demonstrate evidence of the presence of automata-like Anishinaabe symbology encoded into our digital age.” (read complete essay)

TRANSFORMATION BANDOLIER

With Transformation Bandolier, Barry Ace deconstructs the bag down to its essential form. We see all the conventional elements of its structure: strap, pocket panel and fringe. For the work, paper is his material of choice, as though he is patterning a template for the future. For Ace, the decision was deliberate, a way to provoke questions as to why, when fabric would be the obvious option, he would opt to use such a delicate material? The fragility is a meditation on loss, of how things can be easily damaged or destroyed when one’s attention is lacking. (read complete essay)

BANDOLIER FOR NIIMI’IDIWIN (POWWOW)

The construction of earlier bags often included a “secret pocket”. Over time, with the material innovations of the gashkibidaaganag, from woven finger-loomed construction up until the mid-19th century to the appliqué beadwork into the early 20th Century, the pocket altogether disappears, or is intentionally constructed with an opening too small for a human hand. The false pocket is simply a symbol to represent what came before. In Bandolier for Niimi’idiwin Powwow, Ace incorporates his own 21st century adaptation of a gashkibidaagan design. Where a pocket may have been, a digital tablet has been embedded. Here though, what is contained in the “pocket” is no secret. The movement of someone coming within an intimate radius of the bag activates, through an embedded motion detector, images of detailed fragments of dance regalia. The images are Ace’s own digital documentation taken during intertribal dances, the moment when everyone, including the audience, is welcomed into the circle to dance together. (read complete essay)

IMAGE: Fox Tail Moccasins; Photo courtesy of Heffel Fine Art Auction House (view larger)

IMAGE: Fox Tail Moccasins; Photo courtesy of Heffel Fine Art Auction House (view larger)

FOX TAIL MOCCASINS

For Ace, he claims his work is not about “reproducing an object as a replica but rather using the work as a reference or sounding board.” As with much of Ace’s oeuvre, there is a reverent citation of the historical that he builds on to create a contemporary iteration. When viewing Bodmer’s work, as captured by his colonial gaze, “we are looking at a historical stasis,” Ace asserts. Ace’s own work, with its innovative and beautiful use of repurposed electronic components, breaks the colonial confinement to set Indigenous culture into the present. (read complete essay)

IMAGE: Efface; Photo courtesy of Heffel Fine Art Auction House (view larger)

EFFACE

The title, on one hand, connotes colonial erasure; when the meaning is flipped it may also signify the nullification of colonization, presenting an opportunity for regeneration. Ace stated “As Indigenous people, we embraced technology and have always been innovative.” Ace’s modification of these Oxford-style shoes is another stunning example of his ability to Indigenize as well as Indigitize everyday accouterments promenading a distinctive Anishinaabe aesthetic into the 21st century and beyond. (read complete essay)

SYNTHESIS

In this work, Barry Ace explores the meaning of synthesis, “a composition or combination of parts or elements so as to form a whole.”[1]

Ace intentionally combines three types of record-keeping to form a unique configuration. Birch bark and paper, along with electrical components that signify the electronic or digital storing of data, are layered one on top of each other, as though indicating the historical timeline of their introduction into use. (read complete essay)

MANIDOOMINENS LANDSCAPE

Parsing out the many layers of meaning in this work, it is both a biographical reference and a historical commentary. The motif of the stroke of paint bifurcating the white space, bleeding onto the image, is one Ace uses often. “The line is referencing the poignancy of the sharpness of a point that I want to make,” he states. Here, the line cuts into the ominous gray sky of storm clouds converging on the Prairies. It then slashes through the white box cars of a train that Ace notes “ironically looks like a strand of beads referencing the spirit berry but also referencing the seduction of Indigenous people with trade items in perceived exchange for territory.” For Ace, the train also calls to mind Wampum Belts, the beaded leather strands used to signify tribal alliances and treaty agreements to share the land. (read complete essay)

FLUX

In Flux, the third work in the series, Ace concentrates the beadwork within the centre of the circular graph. Here, inside the watery blue outer circle of beadwork, the same blue beads trickle into an inner black disk resembling a circuit board. The meandering estuaries mimic the metallic pathways traced onto the surfaces of a board. It is through these pathways often made of copper – an element of spiritual importance to the Anishinaabe – that energy currents flow, making the connections required to power our 21st century devices. The effect calls to mind a landscape, as witnessed from above, yet it is also an intentional insertion of a common motif by Ace referencing, as well as incorporating, the refuse and e-waste of our digital age. (read complete essay)

MEMORY LANDSCAPE

In Memory Landscape I, a very personal work for Ace that was first exhibited in Braga, Portugal at Museu Nogueira da Silva, 30 scrolls form a complete narrative documenting the seasons of life, and will remain together as an unbroken set. In Memory Landscape II, each of the 30 diptychs from this set stand alone, as Ace continues with images depicting the Manitoulin area, the traditional territory of the Anishinaabeg. Through these lush images, Ace invites us to see this stunning landscape through an Anishinaabe lens. (read complete essay)

IMAGE: Screen cap www.heffel.ca (View larger)

1 Comment

Comments are closed.

[…] The L Project post (here). […]